Freedom of Movement

THE MICHIGAN GUIDELINES ON REFUGEE FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT

Freedom of movement is essential for refugees to enjoy meaningful protection against the risk of being persecuted, and enables them to establish themselves socially and economically as foreseen by the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (“Convention”). The very structure of the Convention presumes the right to leave in search of protection,since a refugee is defined as an at-risk person who is “outside” his or her own country. Once outside the home state, the Convention makes express provision for rights not to be sent away (non-refoulement), to enjoy liberty upon arrival, to benefit from freedom of movement and residence once lawfully present, to travel once lawfully staying, and ultimately to return to the home state if and when conditions allow. Respect for refugee freedom of movement in its various forms is thus central to good faith implementation of the Convention. The right of refugees to move has moreover been reinforced by the advent of general human rights norms in the years since the Convention’s drafting. Of particular importance is the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”), the relevant provisions of which have been authoritatively interpreted to apply equally to citizens and non-citizens, including refugees. Despite the clear legal foundation of refugee freedom of movement at international law, states are also committed to the deterrence of human smuggling and trafficking, to the maintenance of effective general border controls, to safeguarding the critical interests of receiving communities, and to effectuating safe and dignified repatriation when refugee status comes to an end. Legal obligations to respect refugee freedom of movement therefore co-exist with, and must be reconciled to, other important commitments. With a view to promoting a shared understanding of how best to understand the scope of refugee freedom of movement in the modern protection environment we have engaged in sustained collaborative study of, and reflection on, relevant norms and state practice. Our research was debated and refined at the Eighth Colloquium on Challenges in International Refugee Law, convened between March 31 and April 2, 2017, by the University of Michigan’s Program in Refugee and Asylum Law. These Guidelines are the product of that endeavor and reflect the consensus of Colloquium participants on how states can best answer the challenges of implementing the right of refugees to freedom of movement in a manner that conforms with international legal principles.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

1. Refugee status is declaratory. A person becomes a refugee as soon as he or she in fact meets the criteria of the Convention’s refugee definition, not when refugee status is formally recognized. 2. Some Convention rights, including in particular to protection against both refoulement and discrimination and to access a state’s courts, must be respected as soon as a refugee comes under the jurisdiction of a state party. Other Convention rights are defined to apply only once a refugee enters a state’s territory, is lawfully present, is lawfully staying, or durably resides in a state party. Convention rights, once accrued, must be provisionally honored until and unless a final determination is made that the person claiming protection as a refugee is not in fact a refugee.International law requires that treaties be interpreted harmoniously if possible. There is no irreconcilable normative conflict between Convention and ICCPR provisions that define the freedom of movement of refugees, in consequence of which refugees are entitled to claim the benefit of both Convention and ICCPR rights. 3. International law requires that treaties be interpreted harmoniously if possible. There is no irreconcilable normative conflict between Convention and ICCPR provisions that define the freedom of movement of refugees, in consequence of which refugees are entitled to claim the benefit of both Convention and ICCPR rights.

DEPARTURE TO SEEK PROTECTION

4. Refugees, like all persons, are free to leave any country pursuant to Art. 12(2) of the ICCPR. In accordance with Art. 12(3), the freedom to depart may be subjected only to limitations provided by law, implemented consistently with other ICCPR rights, and shown to be necessary to safeguard a state’s national security, public order (ordre public), public health or morals, or the rights and freedoms of others. 5. A limitation is only necessary if shown to be the least intrusive means to safeguard the protected interest. 6. So long as an individual seeking to leave a state’s territory does so freely, meaning that he or she has made an autonomous decision to do so, the state of departure may not lawfully restrict the right to leave on the basis of concerns about risk to the individual’s life or safety during the process of leaving or traveling. 7. International law requires states to prosecute and punish transnational and other organized criminals who engage in human smuggling, that is the procurement of unauthorized entry of a person into another state for a financial or other material benefit. The deterrence of human smuggling may not, however, be invoked to justify a restriction on the right of persons seeking to leave any country. This is because the avoidance of breach of another state’s migration laws or policies does not fall within the scope of the public order (ordre public) exception authorized by ICCPR Art. 12(3), which speaks to an interest of the state invoking the restriction rather than to an interest of another state. 8. International law also requires states to combat human trafficking. In contrast to smuggling, human trafficking is by definition an exploitative practice that harms individuals under the departure state’s jurisdiction. It may thus prima facie engage an interest under ICCPR Art. 12(3). But because the right of everyone to leave a country may only be lawfully restricted if that is the least intrusive means available to pursue even a clearly legitimate interest, state efforts must focus on interrupting the work of traffickers rather than on seeking to stop the departure of would-be refugees and others. This approach aligns with Art. 14 of the UN Trafficking Protocol, requiring anti-trafficking commitments to be pursued in a manner that ensures respect for refugee and other international human rights.

ACCESS TO PROTECTION

9. The duty of non-refoulement set by Art. 33 of the Convention binds a state both inside and at its borders, as well as in any extraterritorial place in which it exercises jurisdiction, whether lawfully or otherwise. The failure of a state agent to hear or to respond to a protection claim made within state jurisdiction that results in a refugee’s return to, or remaining in, a place in which there is a real chance of being persecuted, is an act of refoulement. 10. A good faith understanding of the duty of non-refoulement requires states to provide reasonable access and opportunity for a protection claim to be made. While the mere existence of a natural barrier (eg. a mountain range or river) does not in and of itself amount to an act of refoulement, a state may not lawfully construct or maintain a man-made barrier that fails to provide for reasonable access to its territory by refugees.As more refugees arrive at a state’s border, or as those arriving face more imminent risks, access to protection is reasonable only if it is responsive to such additional or more acute needs. 11. As more refugees arrive at a state’s border, or as those arriving face more imminent risks, access to protection is reasonable only if it is responsive to such additional or more acute needs. 12. The existence of a mass influx of refugees – defined as a situation in which the number of refugees arriving at a state’s frontiers clearly exceeds the capacity of that state to receive and to protect them – may, in an extreme case, justify derogation from one or more Convention or other rights on the basis of the principle of necessity. Derogation based upon necessity may be invoked only if the state faces a grave and imminent peril and must derogate in order to safeguard an essential interest. 13. A state may, however, only invoke necessity where it has not contributed to the peril. It must also continuously assess that peril and its response thereto in order to ensure that the derogation undertaken remains necessary. Because derogation is necessary only if it is the least intrusive response capable of safeguarding the essential interest, the refoulement of refugees will almost invariably be impermissible. More generally, if and when a dependable system of burden and responsibility sharing as envisaged by the Convention’s Preamble is implemented, the conditions precedent for lawful resort to necessity-based derogation are unlikely to be satisfied.

LIBERTY UPON ARRIVAL

14. Refugees entering a state party are immediately entitled to the protection of Art. 9 of the ICCPR, stipulating that everyone has the right to liberty and security of person, and may not be subjected to arbitrary arrest or detention. 15. Detention of a refugee during the very earliest moments after arrival is not arbitrary and therefore does not breach ICCPR Art. 9 so long as such detention is prescribed by law and is shown to be the least intrusive means available to achieve a specific and important lawful purpose, such as documenting the refugee’s arrival, recording the fact of a claim, or determining the refugee’s identity if it is in doubt. 16. Any further detention must be continuously justified on an individuated basis. It is not enough for detention to promote a legitimate government objective, such as ensuring national security, public order (ordre public), public health or morals, or the rights and freedoms of others. Because any limitation on the right to liberty must be demonstrably the least intrusive means available to secure a permissible objective, detention is lawful only if lesser restrictions on liberty – such as reporting requirements or sureties – are incapable of ensuring the permissible objective. 17. Nor may a state routinely subject all refugees to restrictions on liberty that are less intrusive than detention. Under Convention Art. 31(2), a refugee coming directly from a territory where his or her life or freedom was at risk, who has presented himself or herself without delay to authorities, and who has shown good cause for illegal entry or presence is presumptively exempt from any restriction on freedom of movement unless that restriction is shown to be necessary – that is, that it is the least intrusive means available to secure a permissible objective. The requirements of Art. 31(2) must be interpreted in a broad, non-mechanistic, and purposive way.

MOVEMENT AND RESIDENCE

18. A refugee who is lawfully present in a state is entitled under both Convention Art. 26 and ICCPR Art. 12(1) to move freely within that state’s territory and to choose his or her place of residence. A refugee is lawfully present (even if not yet lawfully staying) when he or she has been granted provisional admission or some other form of authorization to be present in the state, including for purposes of the assessment of his or her claim to be a refugee. 19. Once lawfully present, no refugee-specific restriction on freedom of movement or choice of residence is permissible. Under Convention Art. 26, only restrictions also applicable to aliens generally in the same circumstances are lawful. Even if applicable to aliens generally in the same circumstances, ICCPR Art. 12(3) disallows any restriction on movement or choice of residence that is not provided for by law and shown to be the least intrusive means available to ensure national security, public order (ordre public), public health or morals, or the rights and freedoms of others. 20. It makes no difference whether the restriction on freedom of movement or choice of residence results from direct or indirect state action. If, for example, a state were to provide a refugee with the necessities of life in only a specified location, that decision amounts to a restriction on freedom of movement and choice of residence which is lawful only if it meets the requirements of Convention Art. 26 and ICCPR Art. 12. 21. ICCPR Art. 12(3) disallows any restriction on movement or choice of residence that infringes any other right in the ICCPR. As such, an otherwise valid restriction that, for example, poses a risk to a refugee’s physical security by requiring presence or residence in a dangerous location is not lawful. 22. Art. 28 of the Convention authorizes a state to issue a Convention travel document to enable any refugee physically present in its territory to travel abroad. Once a refugee is lawfully staying in a state’s territory, including after formal recognition of his or her refugee status, the state of residence is obliged to issue that refugee with a Convention travel document meeting the requirements of the Schedule to the Convention, unless compelling reasons of national security or public order require otherwise.

RETURN TO ONE’S OWN COUNTRY

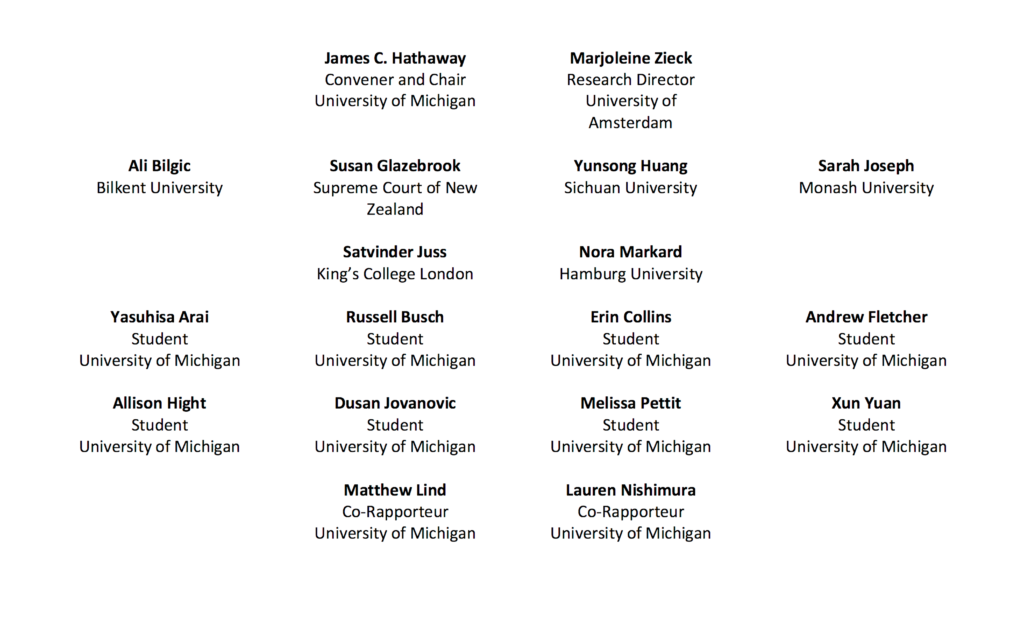

23. Art. 12(4) of the ICCPR provides that no one may be arbitrarily deprived of the right to enter his or her own country. Because a refugee’s “own country” will ordinarily be his or her country of origin, he or she is presumptively entitled to enter that state with a view to attempting voluntary re-establishment there, as well as to be repatriated there consequent to lawful cessation under the Convention. 24. In some circumstances an individual may have more than one “own country.” This may be the case for a refugee who has established special ties to a state of refuge, entitling him or her to claim that state as one of his or her “own countries.” While this would in principle be grounds for a former refugee subject to repatriation to contest his or her removal from the state of refuge, such a claim should not ordinarily prevail. This is because ICCPR Art. 12(4) only prohibits the arbitrary deprivation of the right to enter (and by implication, to remain in) one’s own country. The repatriation of a person whose refugee status has ceased in line with the requirements of the Convention is normally not arbitrary, since it is consistent with the Convention’s object and purpose of ensuring protection only for the duration of risk in the country of origin. 25. A (present or former) refugee’s “own country” must ordinarily authorize readmission to its territory. In the rare instance where there is an official declaration by that country that mass return or repatriation poses a threat to the life of the nation – for example, where the state’s basic infrastructure has been decimated by war and cannot yet support a major population increase – ICCPR Art. 4(1) allows that state provisionally, without discrimination, and to the extent strictly necessary, to derogate from its duty of readmission. Measures derogating from the provisions of the Covenant must, however, be of an exceptional and temporary nature. As such, derogation will not justify an indefinite bar to entry but only a delay of entry to the extent strictly required by the exigencies of the emergency. These Guidelines reflect the consensus of the undersigned, each of whom participated in their personal capacity in the Eighth Colloquium on Challenges in International Refugee Law, held at Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, on March 31–April 2, 2017.

The Colloquium deliberations benefited from the counsel of Madeline Garlick, Chief of Protection Policy and Legal Advice Section, Division of International Protection, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.